What's With the Athletics' Elephant Mascot?

When you look back at Connie Mack's time in Philadelphia, you see a lot of elephants. There were elephant on the Athletics' uniforms. There were elephants on the hats. Connie Mack had elephant statues. There was an elephant in the Athletics' logo. The A's Christmas cards even had an elephant. Now, most fans of Philadelphia baseball history can tell you that the elephant originated from a comment by John McGraw, the famous manager of the New York Giants. He called the Philadelphia Athletics a white elephant. Connie Mack was so amused by the comment, that he adopted the white elephant as the team's mascot. But, what exactly does all of this mean?

White elephants were revered in southeast Asian culture. They were seen as a sign of wealth and opulence. Rulers kept white elephants as a symbol of their power. Because white elephants were revered, they were protected from performing labor. But this meant that a gift of a white elephant from the ruler was seen as a blessing and a curse. On the one hand, it was an honor to be given one of these majestic creatures. On the other, the upkeep of the animal was wildly expensive. Moreover, the owner of the white elephant could not use the beast to earn money to pay for its own maintenance.

Because of this, the term "white elephant" came to signify something that is very attractive, but was highly expensive. Indeed, the cost of maintaining the object was disproportionate to its usefulness. Because of its high cost, a "white elephant" was something that was not easily sold or disposed of.

So, how did this concept apply to the Philadelphia Athletics?

In 1895, Byron Bancroft "Ban" Johnson became the President of the Western League. This was a minor league composed mostly of baseball teams in the Great Lakes region. Johnson wanted to enhance the prestige of the league, and convert it into a major league to rival the National League. Beginning in the 1900 season, Johnson renamed the league, the American League, and moved franchises into major cities which were abandoned by the National League. After the 1900 season, Johnson withdrew the American League from the National Agreement, which established the relationship between the National League and the minor leagues. He declared the American League to be a major league, and placed more teams in major metropolitan areas.

In order to attract top talent, the American League teams took advantage of the National League's limit on players' salaries of $2,400. By offering higher pay, the American League teams encouraged disgruntled players to jump leagues. That is, the new American League teams essentially raided the National League for its talent.

Connie Mack was recruited to manage the new Philadelphia Athletics of the American League. He convinced sporting goods magnate Benjamin Shibe to become a 50% owner of the A's. Mack would own 25% of the team. The remaining 25% would be slip between sportswriters Sam Jones and Frank Hough.

Like other American League teams, Mack raided the National League for its roster. In particular, Mack targeted disgruntled players from the A's cross-town rivals, the Philadelphia Phillies. Colonel John Rogers had a reputation of being a particularly stingy owner. Indeed, Rogers had a falling out with co-owner, Al Reach in 1899 over the direction of the team, which resulted in Reach divesting himself of his ownership interest in the Phillies. Reach was a well-known superstar of the original Philadelphia Athletics teams in the mid-1860s, who started a sporting goods business. In fact, Reach would become the exclusive supplier of baseballs to the American League, manufacturing those baseballs in a factory in the Fishtown neighborhood of Philadelphia.

It was because of Rogers' stinginess, that five Phillies players were willing to make the jump to the Athletics in 1901. They were Nap Lajoie, Joe Dolan, Morgan Murphy Bill Bernhard and Wiley Piatt. Of those players, Lajoie was the main prize, as he was the best hitter on the Phillies team. Lajoie went from a salary of $2,600 in 1900 with the Phillies, to $4,000 in 1901 with the Athletics, and then $7,000 in 1902. Lajoie would also go on to compete annually for the batting title in the American League.

Soon, more Phillies jumped leagues to join their counterparts in the American League. By the end of 1901, the Athletics added future Hall of Fame outfielder Elmer Flick, and shortstop Monte Cross. Star slugger and future Hall of Famer Ed Delahanty also left the Phillies. However, Big Ed signed to play with the Washington Senators.

Colonel Rogers, however, did not take losing his star players to the upstart Athletics lying down. He sued those Phillies who had left his team to play for the Athletics in Pennsylvania court for breach of contract. This included the high-priced superstar Nap Lajoie. Rogers won the lawsuit, which included an injunction preventing Lajoie and his former Phillies teammates from playing professional baseball for any team other than the Phillies.

The judgment that Rogers won, however, was only enforceable in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. To address the problem, Mack orchestrated a trade with the American League club in Cleveland. Soon, Lajoie, Flick and Bill Bernhard were playing for the Cleveland, who changed their name from the Bluebirds to the Naps. The only caveat was that the former Phillies could not join the team when Cleveland played road games against the Athletics.

With this background in mind, stepped John McGraw. McGraw was actually hired to manage the Baltimore Orioles of the new American League in 1901 and 1902. McGraw was known for being an outspoken critic of the umpires. One incident earned McGraw a suspension at the end of June of 1902. McGraw had learned that Ban Johnson had planned to move the Orioles to New York to compete with the National League's Giants, and that nother person had been promised the job of manager once the team moved.

During his suspension, McGraw, therefore, negotiated with the Giants and was offered the job of manager. He approached the Orioles' Board of Directors, and offered to forgive them the money he was owed as their manager, if they would release him from his contract. The Orioles agreed. The deal between McGraw and the Giants was then announced on July 7th.

On July 11th, McGraw was quoted in the Washington Times as saying that Ben Shibe had a white elephant on his hands, with respect to the Athletics. Specifically, Mc Graw said, "The Philadelphia club is not making any money. It has a big white elephant on its hands."

This was a specific reference to the fact that Shibe was paying $7,000 per year for the Athletics to play their home games at the Jefferson Street Grounds. With such expenses, McGraw did not think the A's could make enough money to turn a profit.

But McGraw could have just as easily been referring to the Athletics' personnel problems. They had lured key players away with big contracts, only to lose them in a trade made necessary by litigation. Meanwhile, the Athletics had almost certainly incurred legal expenses defending against Rogers' lawsuit.

The American and National League eventually negotiated a peace in 1903. The Orioles suffered attrition, as players left the team, which came to a head on July 17th, when the Orioles only had five players, and thus not enough to field a team to play a game against the St. Louis Browns. The Orioles' players had umped ship for the National League. The Orioles forfeited that game, and the Board of Directors forfeited their franchise to the American League. In 1903, the League moved the franchise to New York, and called it the Highlanders. This would eventually become the famed New York Yankees.

But the two leagues realized that they could not continue poaching players from each other, and therefore agreed to recognize the sanctity of each others' players' contracts. The result of that peace ushered in a new World Series, which pitted the winners of the pennants of the two leagues against each other for the championship of professional baseball.

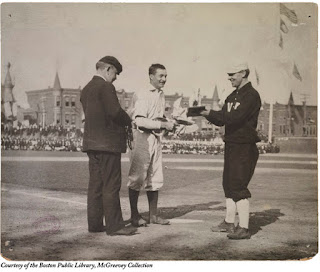

In 1904, McGraw, whose Giants had won the NL pennant, refused to play the AL pennant winning Boston Americans. In 1905, however, both leagues drafted rules to compel their respective pennant winners to play in the World Series. That year, the Athletics won their second American League pennant, the first coming in 1902, the year before the World Series was re-introduced to baseball. The Giants also won the NL pennant. When the two teams met in the 1905 World Series, the Athletics presented McGraw with a white elephant statuette. The white elephant has since become an enduring feature of Athletics lore. Indeed, the white elephant continued to be part of the Athletics' logo, even when the team moved to Kansas City until 1965. After moving to Oakland, the Athletics reintegrated the white elephant into their logo in 1988.

By: William J. Kovatch, Jr.

Show pride in your hometown baseball history by checking out our merch store! Now offering stylish Phillies-themed face masks!! Protect the health of you and your family, while showing Phillies pride. https://www.teepublic.com/user/philadelphia-baseball-history

Check out our YouTube Channel at: YouTube.com/c/PhiladelphiaBaseballHistory

You can find the YouTube video of this article here: https://youtu.be/EeGPUVOj7yQ

You can also find us on Twitter, @PhilBaseballHis, and Instagram.

"The A's and Their Elephants, Together Since July 10, 1902," Todd Radom Designs (May 2, 2016).

Goodtimes, Johnny, "John McGraw and the White Elephants," Philly Sports History (October 27, 2011).

"Napoleon Lajoie: How Major League Baseball made legal history," The State Museum of Pennsylvania (March 22, 2016).

Rogers III, C. Paul, "Napoleon Lajoie, Breach of Contract and the Great Baseball War," SMU Law Review (Volume 55, 2002).

Silberman, Max, "A Short History of the Philadelphia Athletics," Rooted in Oakland (site visited July 14, 2020).

Thorn, John, "The House That McGraw Built," Our Game (February 29, 2012).

White elephants were revered in southeast Asian culture. They were seen as a sign of wealth and opulence. Rulers kept white elephants as a symbol of their power. Because white elephants were revered, they were protected from performing labor. But this meant that a gift of a white elephant from the ruler was seen as a blessing and a curse. On the one hand, it was an honor to be given one of these majestic creatures. On the other, the upkeep of the animal was wildly expensive. Moreover, the owner of the white elephant could not use the beast to earn money to pay for its own maintenance.

Because of this, the term "white elephant" came to signify something that is very attractive, but was highly expensive. Indeed, the cost of maintaining the object was disproportionate to its usefulness. Because of its high cost, a "white elephant" was something that was not easily sold or disposed of.

So, how did this concept apply to the Philadelphia Athletics?

In 1895, Byron Bancroft "Ban" Johnson became the President of the Western League. This was a minor league composed mostly of baseball teams in the Great Lakes region. Johnson wanted to enhance the prestige of the league, and convert it into a major league to rival the National League. Beginning in the 1900 season, Johnson renamed the league, the American League, and moved franchises into major cities which were abandoned by the National League. After the 1900 season, Johnson withdrew the American League from the National Agreement, which established the relationship between the National League and the minor leagues. He declared the American League to be a major league, and placed more teams in major metropolitan areas.

In order to attract top talent, the American League teams took advantage of the National League's limit on players' salaries of $2,400. By offering higher pay, the American League teams encouraged disgruntled players to jump leagues. That is, the new American League teams essentially raided the National League for its talent.

Connie Mack was recruited to manage the new Philadelphia Athletics of the American League. He convinced sporting goods magnate Benjamin Shibe to become a 50% owner of the A's. Mack would own 25% of the team. The remaining 25% would be slip between sportswriters Sam Jones and Frank Hough.

Like other American League teams, Mack raided the National League for its roster. In particular, Mack targeted disgruntled players from the A's cross-town rivals, the Philadelphia Phillies. Colonel John Rogers had a reputation of being a particularly stingy owner. Indeed, Rogers had a falling out with co-owner, Al Reach in 1899 over the direction of the team, which resulted in Reach divesting himself of his ownership interest in the Phillies. Reach was a well-known superstar of the original Philadelphia Athletics teams in the mid-1860s, who started a sporting goods business. In fact, Reach would become the exclusive supplier of baseballs to the American League, manufacturing those baseballs in a factory in the Fishtown neighborhood of Philadelphia.

It was because of Rogers' stinginess, that five Phillies players were willing to make the jump to the Athletics in 1901. They were Nap Lajoie, Joe Dolan, Morgan Murphy Bill Bernhard and Wiley Piatt. Of those players, Lajoie was the main prize, as he was the best hitter on the Phillies team. Lajoie went from a salary of $2,600 in 1900 with the Phillies, to $4,000 in 1901 with the Athletics, and then $7,000 in 1902. Lajoie would also go on to compete annually for the batting title in the American League.

Soon, more Phillies jumped leagues to join their counterparts in the American League. By the end of 1901, the Athletics added future Hall of Fame outfielder Elmer Flick, and shortstop Monte Cross. Star slugger and future Hall of Famer Ed Delahanty also left the Phillies. However, Big Ed signed to play with the Washington Senators.

Colonel Rogers, however, did not take losing his star players to the upstart Athletics lying down. He sued those Phillies who had left his team to play for the Athletics in Pennsylvania court for breach of contract. This included the high-priced superstar Nap Lajoie. Rogers won the lawsuit, which included an injunction preventing Lajoie and his former Phillies teammates from playing professional baseball for any team other than the Phillies.

The judgment that Rogers won, however, was only enforceable in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. To address the problem, Mack orchestrated a trade with the American League club in Cleveland. Soon, Lajoie, Flick and Bill Bernhard were playing for the Cleveland, who changed their name from the Bluebirds to the Naps. The only caveat was that the former Phillies could not join the team when Cleveland played road games against the Athletics.

With this background in mind, stepped John McGraw. McGraw was actually hired to manage the Baltimore Orioles of the new American League in 1901 and 1902. McGraw was known for being an outspoken critic of the umpires. One incident earned McGraw a suspension at the end of June of 1902. McGraw had learned that Ban Johnson had planned to move the Orioles to New York to compete with the National League's Giants, and that nother person had been promised the job of manager once the team moved.

During his suspension, McGraw, therefore, negotiated with the Giants and was offered the job of manager. He approached the Orioles' Board of Directors, and offered to forgive them the money he was owed as their manager, if they would release him from his contract. The Orioles agreed. The deal between McGraw and the Giants was then announced on July 7th.

On July 11th, McGraw was quoted in the Washington Times as saying that Ben Shibe had a white elephant on his hands, with respect to the Athletics. Specifically, Mc Graw said, "The Philadelphia club is not making any money. It has a big white elephant on its hands."

This was a specific reference to the fact that Shibe was paying $7,000 per year for the Athletics to play their home games at the Jefferson Street Grounds. With such expenses, McGraw did not think the A's could make enough money to turn a profit.

But McGraw could have just as easily been referring to the Athletics' personnel problems. They had lured key players away with big contracts, only to lose them in a trade made necessary by litigation. Meanwhile, the Athletics had almost certainly incurred legal expenses defending against Rogers' lawsuit.

The American and National League eventually negotiated a peace in 1903. The Orioles suffered attrition, as players left the team, which came to a head on July 17th, when the Orioles only had five players, and thus not enough to field a team to play a game against the St. Louis Browns. The Orioles' players had umped ship for the National League. The Orioles forfeited that game, and the Board of Directors forfeited their franchise to the American League. In 1903, the League moved the franchise to New York, and called it the Highlanders. This would eventually become the famed New York Yankees.

But the two leagues realized that they could not continue poaching players from each other, and therefore agreed to recognize the sanctity of each others' players' contracts. The result of that peace ushered in a new World Series, which pitted the winners of the pennants of the two leagues against each other for the championship of professional baseball.

In 1904, McGraw, whose Giants had won the NL pennant, refused to play the AL pennant winning Boston Americans. In 1905, however, both leagues drafted rules to compel their respective pennant winners to play in the World Series. That year, the Athletics won their second American League pennant, the first coming in 1902, the year before the World Series was re-introduced to baseball. The Giants also won the NL pennant. When the two teams met in the 1905 World Series, the Athletics presented McGraw with a white elephant statuette. The white elephant has since become an enduring feature of Athletics lore. Indeed, the white elephant continued to be part of the Athletics' logo, even when the team moved to Kansas City until 1965. After moving to Oakland, the Athletics reintegrated the white elephant into their logo in 1988.

By: William J. Kovatch, Jr.

Show pride in your hometown baseball history by checking out our merch store! Now offering stylish Phillies-themed face masks!! Protect the health of you and your family, while showing Phillies pride. https://www.teepublic.com/user/philadelphia-baseball-history

Check out our YouTube Channel at: YouTube.com/c/PhiladelphiaBaseballHistory

You can find the YouTube video of this article here: https://youtu.be/EeGPUVOj7yQ

You can also find us on Twitter, @PhilBaseballHis, and Instagram.

References

"The A's and Their Elephants, Together Since July 10, 1902," Todd Radom Designs (May 2, 2016).

Goodtimes, Johnny, "John McGraw and the White Elephants," Philly Sports History (October 27, 2011).

"Napoleon Lajoie: How Major League Baseball made legal history," The State Museum of Pennsylvania (March 22, 2016).

Rogers III, C. Paul, "Napoleon Lajoie, Breach of Contract and the Great Baseball War," SMU Law Review (Volume 55, 2002).

Silberman, Max, "A Short History of the Philadelphia Athletics," Rooted in Oakland (site visited July 14, 2020).

Thorn, John, "The House That McGraw Built," Our Game (February 29, 2012).

Comments

Post a Comment